A BrazilWorks Review of:

Brazil’s Rise: Seeking Influence on Global Governance

Harold Trinkunas

Latin American Initiative

Foreign Policy-Brookings Institution

April 2014

Harold Trinkunas, Senior Fellow and Director, Foreign Policy and Latin America Initiative at the Brookings Institution, offers up a relevant, lucid analysis of Brazil and its contemporary foreign policy options with respect to global governance issues. For Trinkunas,

“Brazil stands at the crossroads in its road to major power status. It can either continue its ascent, or can remain a middle power, albeit a critical one, within the existing international status quo.”

Brazil’s future has always attracted a lot of attention by scholars, journalists, and foreign policymakers; but is particularly relevant in 2014 when Brazil hosts the FIFA Men’s Soccer Championship (the largest sporting event on earth) and carries out its presidential elections. Trinkunas breaks down his analysis into distinct questions about Brazil’s intentions, its capabilities, and opportunities to rise toward major power status. He does not treat in any detail what the international status quo is and its impact on Brazilian development, nor does he integrate parallel arguments regarding Brazil as a global swing state or its role in the “rise of the rest” thesis. Trinkunas does recognize that the United States’ “post-Cold War unilateral moment” is on the wane, but does not clearly explain how the current global balance of power shapes Brazil’s foreign policy choices or challenges.

Few doubt that Brazil’s global political influence has increased during the past two decades-partially the consequence of domestic policies that achieved growth, income redistribution, and stability along with former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s pronounced presidential diplomacy. Brazilian foreign policymakers do seek to change the world, rebalance the global balance of power, and reform international intergovernmental institutions of global and regional governance, but it is unclear whether their intentions are to climb the last rungs of the global power ladder or work to help pull up the rest. Even if Brazilian political leaders chose the former, does the country have sufficient capabilities and would the Brazilian electorate support such a strategy at the ballot box?

We can learn a lot from Trinkunas’ analysis, but his perspective on Brazilian efforts to exert global power relies on too many historical assumptions about Brazil’s motivations and how they serve to shape the nation’s foreign policy. He makes the claim that Brazil “sought admittance to great power status through allying with the leading powers of the system” following World War II (pp.9). Trinkunas correctly reports that important U.S. foreign policymakers, including President Roosevelt, sought to incorporate Brazil within a global party of liberal internationalism following the conclusion of WWII. Yet there is little evidence that such policymakers wanted to raise Brazil to the righteous rungs of the global power ladder. Rather, they understood Brazil as a major producer of raw materials, a consumer of U.S. exports, and an anti-communist battleground. Despite these reasons, U.S. foreign policymaking after WWII, as Trinkunas reports, frustrated Brazil by its utter lack of sensibility and commitment to the national development priorities of Brazilian democratic populism.

Certainly Brazilians of many political persuasions were disappointed with bilateral relations following Brazil’s alliance with the U.S. and direct military collaboration during the latter stages of WWII, but this does not prove that Brazilian policymakers were eager to obtain the regalia of global leadership and pay its compulsory costs. Rather, most Brazilian leaders, from Getúlio Vargas to Lula, were deeply focused on national economic development and willing to strike alliances with those in a position to assist the most. Despite differences in political tone and policy preferences, Brazilian leaders and political parties share a fundamental consensus on the importance of economic development and the key role of the state in leading the way. Trinkunas also recognizes this feature of twentieth century Brazilian public policymaking, reporting that,

“The military also supported rapid economic development and pursued a largely peaceful foreign policy during its time in power, policy preferences shared by diplomatic and economic elites (pp. 11).”

As Trinkunas concludes, everyone wanted to foment Brazil’s “rise” and take credit for it. Yet, most Brazilian policymakers and leaders understood “rise” in the twentieth century as economic development commensurate with Brazil’s geographical size and natural resources, not so much scaling the rungs of global governance unless it was a pragmatic requirement for advancing national development. Even former President Lula, regarded for his assertive foreign policies, called for a

“new global economic and trade order [that] mirrors the country’s renewed self-confidence as a non-conformist power. It [Brazil] doesn’t seek simply to take up a place at the top table. Rather, it is confident in its strength as a consensus-builder within the South and bridge-builder to the North.”

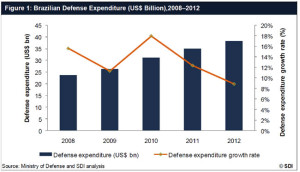

Trinkunas fittingly recounts that Brazil’s geopolitical position does not rely on the bomb or other traditional dimensions of hard power associated with flying over the global power curve without stalling. His comparative analysis of Brazilian defense and military spending is convincing this way. If Brazil is reaching for the top, it is not with offensive weapons. Moreover, he points out that Brazil’s foreign assistance budget and its willingness to “pay off” other states for political cooperation are limited. These empirical dimensions of foreign policy are very telling with respect to motivation and vision. If Brazil does not have much “skin in the game,” then how might one argue that it has repeatedly undertaken concerted efforts to become a major power?

One might argue, as Trinkunas does, that Brazil has faced recent opportunities to harness existing capabilities (mostly expressions of soft power to use Nye’s term) to make a move to rapidly increase its geopolitical influence. He points to Brazil’s “ascendency” in South America as well as the transition from the unipolar moment in U.S. hegemony following the fall of the Soviet Union to “greater multipolarity” over the past decade. However, he flips the argument around to suggest that Brazil’s failure to galvanize support around Latin America (Argentina and Mexico) for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and the U.S. success in incorporating Mexico and Colombia into its geopolitical orbit despite its own decline indicates Brazilian failure to ascend.

This argument stands in contrast to Brazilian foreign ministry officials’ caution in asserting too much leadership in South America and around the LAC region. From all indications and political pronouncements, Brazilian leaders prefer to deepen strategic partnerships with Argentina and Mercosul while expanding alliances around the LAC region without imposing its own blueprint or stepping on toes. This foreign policy framework fits into Brazil’s multilateralist convictions and its own national interest in building consensus around reform of liberal international institutions of global governance that increase representation of the developing world, not Brazilian geopolitical power exclusively. This distinction is essential. For most Brazilian leaders under democratic rule, making global governance more representative is the most constructive avenue for advancing Brazilian national interests, most of which correspond to the economic and social development of the LAC region as well as Africa and other developing or low-income regions of the world.

Trinkunas correctly notes that Brazil’s multilateral efforts and initiatives are slow to develop and do not challenge Brazil’s capabilities or impose substantial costs. Rather than assume that such a relatively slow process is further evidence of Brazil’s failure to seize the moment to rise, another argument would tender that IIRSA, UNASUR, and CELAC are products of consensus building, albeit imperfect, but better suited to the historical convergence of LAC nations eager to cooperate among themselves as one more hedge against a global political economy that offers scarce opportunities to rapidly increase national wealth through participation in global production chains bent on efficiently extracting natural resources, trading agricultural and mineral commodities, exploiting relatively cheap industrial labor, and more recently, penetrating the region’s swelling consumer markets.

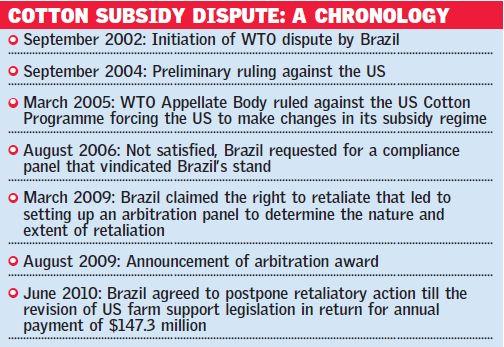

Brazilians are weary of their own inabilities to overcome national bottlenecks to further economic and social development, but few are blind to the very real limits placed on such development by international economic and political factors well beyond their control. Indeed, Brazilian foreign policy has emphasized the importance of addressing these limits through democratic reforms at the International Monetary Fund and better regulation of European and United States banks in recent years for obvious reasons. Moreover, Brazil’s trade policy agenda seeks market access concessions that would improve the developing world’s ability to respond to economic opportunities-largely in the face of U.S. political opposition-including ongoing violations of World Trade Organization agreements (such as the Cotton Dispute among others).

Brazil’s current capabilities and level of economic development are not fully determined by U.S. policy or the institutions of global governance, but there are observable, external limits to Brazil’s rise. If opportunities do exist for Brazil to join the club of super powers, the costs associated with overcoming these external obstacles may not be worth the benefits or be supported by a majority of Brazilians who continue to demand more focused policy attention on national economic development, including better public education and healthcare. During the coming decade it is more likely that elected leaders will opt for greater investments in these basic public services than spend on geopolitical power capabilities in order to seek reelection.

While I disagree with Trinkunas’ fundamental question about whether Brazil will choose to ascend or stick it out as a “critical” middle power, his U.S. foreign policy recommendations are helpful for advancing a more constructive and productive bilateral relationship. As he advocates, Brazil should contribute more resources, from international peacekeeping to humanitarian assistance, to project its national values, competencies, and its own multilateralist, consensus-building international strategies. Brazil may also benefit from scaling back the number of its multilateral initiatives to better focus on the most important. Certainly President Dilma has pulled back from former President Lula’s ambitious agenda in Africa, and it appears that her intensifying concern over the economy and fiscal policies leaves her little time to ponder geopolitics.

Will Brazil’s foreign policy principals change anytime soon? No, nor would U.S. interests be served by a rapid reorientation of Brazil’s international strategies. The long term, national interests of the U.S. are best served by working with Brazil to strengthen international economic and security regimes through consensus rather than imposition. The U.S. should understand that Brazil’s interest in anchoring collective security efforts in the South Atlantic is an opportunity, not a danger. Moreover, U.S. international economic policies, largely framed by the rhetoric of “competitive” capital and trade liberalization, continue to thwart market driven development around the developing world and fall painfully short of providing global leadership. Without significant changes in U.S. policies, it is unlikely that Brazil will concede to U.S. policy preferences, preferring to work with others, including the BRICS and IBSA, to stake out its principles of international economic governance and seek reforms that redistribute global market opportunities.

Trinkunas teaches us plenty about Brazil and the world. No doubt that Brazil has risen in global stature and economic importance. Brazil will likely rise in the future, although the pace is likely to be determined more by international economic factors than deep reforms in domestic policymaking. Brazil also seeks to become more influential in global governance matters, yet progress here depends on continued economic growth and development as well as an increasing willingness to spend more national resources on the creation of international public goods.

Do Brazilians share a thirst for major power status? Certainly some observers, including Trinkunas, might infer that Brazil’s active multilateralism reflects a consensus around doing what it takes to get to the center of the bargaining table on the most important issues facing global governance. No one would dispute that Brazil seeks dramatic changes in the institutions of international cooperation and law, and the foreign ministry works awfully hard to take advantage of every opportunity within sight. Yet, this does not mean that Brazil and its own representative institutions of governance are gearing up to project the nation as a major power anytime soon.

Yes, Brazil sits uncomfortably between the developed and the developing world with a penchant for the former and a political conviction to work closely with the latter. Expect Brazil to increase its contributions to “shaping and enforcing the rules that govern international order,” but mindful not to challenge the global power curve with a strategy that stalls its capacity to build international coalitions around democratic reforms of the institutions and rules that serve to entrench the status quo. The more relevant question is whether Brazilian foreign policymakers are improving the country’s capabilities with respect to incorporating more and more nations into global decision making to offer expanding opportunities for development through global trade and investment. Trinkunas’ assumption may be correct. Brazilians might be better off if the nation pursued major power status, but there is an equally compelling argument that Brazil’s current strategy is best suited to the majority of Brazilians who elect their governments to improve education and healthcare-at least for now.

Mark S. Langevin, Ph.D.

Director, BrazilWorks

June 3, 2014